Work, Sex, Exile and Exofiction

Swedish Literature Exchange asked critic Kristina Lindquist to bring us up to date on the latest themes and tendencies in Swedish fiction. How is current fiction depicting the world of today?

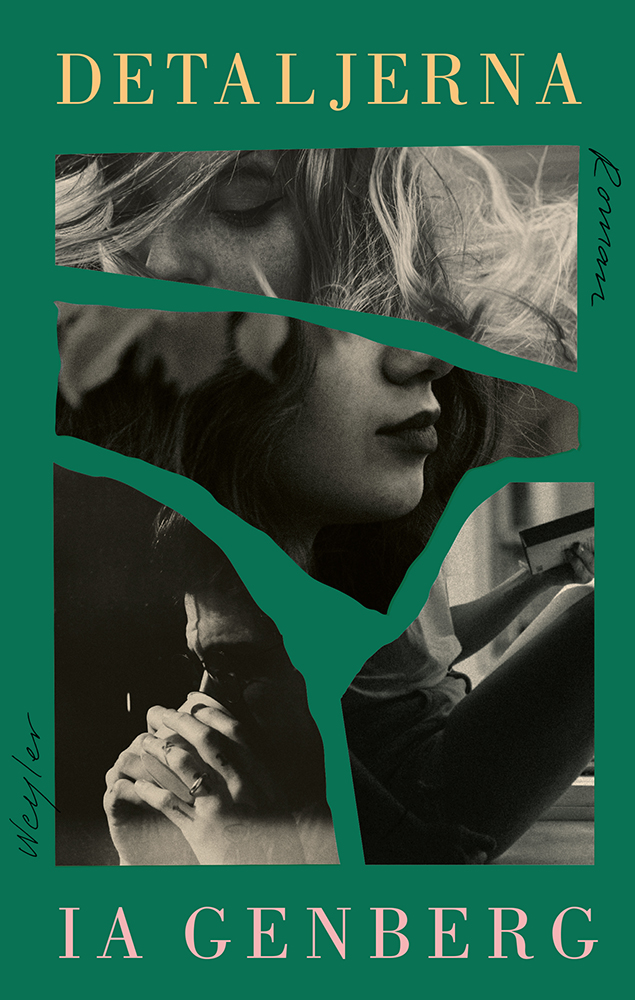

‘So you wrote about cancer; that doesn’t make it art.’ So went the headline of one of the most widely discussed Swedish book reviews of recent years, a piece by critic Linda Skugge about Kristina Sandberg’s novel En ensam plats (A Lonely Place, Norstedts, 2021). Skugge’s review is certainly idiosyncratic, perhaps even vicious, but she has a point. There is a lot of illness going around in fiction right now. Cancer, dementia, post-partum depression – and of course, raging fever, as in Ia Genberg’s exquisite Detaljerna (The Details; Weyler, 2022). What the lasting effects of the Covid-19 pandemic will be on literature remain to be seen. It seems likely that authors will be taking a fresh look at topics such as intimacy, distance, contagion and human contact. In the meantime, we can turn our attention to a few already conspicuous tendencies.

Disillusioned working-class fiction

Working-class fiction is generally seen as a backbone of Swedish publishing. Indeed, it has been called Sweden’s great contribution to the world literary stage. Few will have failed to notice that working-glass fiction is currently enjoying an expansive golden age, ushered in by titles such as Åsa Linderborg’s Mig äger ingen (Nobody Owns Me; Atlas, 2007) and Kristian Lundberg’s Yarden (The Yard; Symposion, 2009). In a recent book examining this trend (Arbetarlitteraturens återkomst/The Return of Working-Class Literature; Verbal Förlag, 2020), Rasmus Landström describes Lundberg’s novel as a gateway novel to a third wave of working-class fiction that focuses on modern day-labourers, downward social mobility and a fragmented labour movement suffused by a sense of ‘powerlessness and class hatred’. Where twentieth-century working-class fiction was grounded in the popular movements of the day, today’s entries in the genre are being written in an ‘ideological headwind’. Landström cites a comment by poet Johan Jönson: ‘The radical progressivism of the Enlightenment has been defeated by the indifferent atheism of the material’. These days, nobody is climbing toward the light.

It seems, moreover, that the bleak view of the future offered in today’s working-class fiction is also affecting how we view the past. We might contrast the classic Stad (Stockholm) series by Per Anders Fogelström, which traced a century in the life of a working-class family beginning in 1860, with Susanna Alakoski’s recent suite of novels about Finnish migrant workers in the 1900s. Fogelström’s novels project a powerful belief in the future, even in the midst of suffering and hardship. Alakoski’s Londonflickan (The London Girl, Natur & Kultur, 2021), the second book in her suite, is set in the postwar period and describes an era of dazzling optimism through a perennially disillusioned, contemporary lens. Her approach conjures a sense of melancholy at the heart of ‘swinging London’.

Another important difference between old and new working-class fiction concerns the nature of the work being portrayed. We have left behind the farm workers, the factory floor reporters and the maids with their buckets and entered the new robotic reality of the white-collar worker. The class lines between job categories have also started to blur. As we see in Elise Karlsson’s Linjen (The Line; Natur & Kultur, 2018), the modern precariat includes both teachers and office workers. It is telling, too, that in one of the most distinctly materialistic novels of recent years, the main character is a glamourous influencer. Tone Schunesson’s Dagarna, dagarna, dagarna (Days and Days and Days; Norstedts, 2020) captures the fluid identity of the modern working class and takes us into a world where every interaction becomes a transaction. Finally, it is notable that most new working-class literature is being written by women. Landström notes the overwhelming preponderance of women among debut authors of working-class fiction in the 2010s and attributes it to the feminisation of the workforce since the 1980s. Another reason is likely an ongoing and widely discussed feminisation of the book industry itself.

Women writing about sexual disenchantment

At least one other current literary trend is also dominated by women. ‘Why,’ wondered literature professor Sven Anders Johansson in early 2021, ‘do women write so much about sex?’ Johansson notes that in their books, female writers like Helena Granström, Maria Maunsbach and Sofia Rönnow Pessah dwell on (fairly violent) sex. Meanwhile, their male colleagues are keeping their mouths shut. Says Johansson: ‘The default subject – the person with the power to express their point of view – used to be masculine. In this particular context [i.e., sex], it almost appears now that the opposite is true’ (Aftonbladet, 10 February 2021). Some voices in the debate have suggested that women authors might naturally use literary sexuality as part of a project of liberation. Others have alleged the existence of a moralistic viewpoint among the cultural public that makes it harder for men to write about sexual situations in which questions of responsibility (or culpability) are not clear-cut.

It is also striking how often sexuality is often used to express something other than pure desire. Johan Thente, literary editor at Dagens Nyheter, suggested recently in New Swedish Books (May 2020) that young women authors are writing about sex as ‘rage, power play, existential provocation or life crisis. Another idea that is often advanced is that sexuality in our day has undergone what German sociologist Max Weber called a process of ‘disenchantment’, rendering sex a completely ‘transparent’ phenomenon. The sex scenes in Isabelle Ståhl’s Just nu är jag här (Right Now I’m Here; Natur & Kultur, 2017) indeed serve as a means of portraying an alienated state. In Wera von Essen’s Våld och nära samtal (Violence and Other Conversations; Natur & Kultur, 2020), however, violent BDSM sex becomes a kind of substitute for religious yearning and consummation. Meanwhile, in the witty diary novel Halva Malmö består av killar som dumpat mig (Half of Malmö Consists of Guys Who Dumped Me; Natur & Kultur, 2021), debut author Amanda Romare wanders in a sexual wilderness with a dating app as an unreliable compass. Romare’s narrator expresses an existential fear of being shut out of the world if she fails to ‘meet someone’. Her sexuality becomes a way in which she holds on to the world of the living.

Exofiction as life raft

Perhaps it is that same need to feel the pulse of life that occupies the writers of so-called exofiction – trying to keep their characters in the realm of the living. The term exofiction, coined in France, refers to a type of fictionalised biography that, to quote translator Helena Fagertun, ‘in contrast to the introversion and self-centring of autofiction turns its gaze outward toward another person, so placing historical reality within a fictional frame’ (Ord & Bild, 19 May 2021). Although exofiction is by no means a dominant trend in Swedish publishing, a few attention-grabbing recent novels fall into this genre. Elin Cullhed’s August Prize-winning novel, Eufori (Euphoria, Wahlström & Widstrand, 2019), for example, centres on the iconic author Sylvia Plath, while Steve Sem-Sandberg’s W takes on the enigmatic historical figure of Johan Christian Woyzeck. Several of Sara Stridsberg’s books probably also count as exofiction, including Drömfakulteten (UK: Faculty of Dreams; US: Valerie, Albert Bonniers, 2006), about Valerie Solanas, and Kärlekens Antarktis (The Antarctica of Love, Albert Bonniers, 2018), which names no names but whose parallels to a famous murder by dismemberment are impossible to miss. The French writer Alexandre Gefen has suggested that exofiction represents, at least in part, an authorial impulse to ‘repair the world’ by placing literature above an unbearable reality. Or perhaps it is simply as writer Märta Tikkanen once said: ‘Everything is material; life is material.’

Exile and longing for home and away

Finally, we must mention the important recent books about the conditions and experience of exile. The theme of flight or escape is, of course, not a literary ‘trend’, but rather one of literature’s enduring concerns. As writer Kristoffer Leandoer notes, ‘our Western literature was born and still draws its lifeblood’ from the tension between the desire to stay and the desire to go. But we are undeniably seeing a profusion of books right now that give a face and voice to exile and its descendants. Three 2021 titles offer a snapshot of current concerns. In Balsam Karam’s Singulariteten (The Singularity; Norstedts, 2021), three interwoven narratives tell a story of loss, flight and alienation, where the boundless grief of the individual is connected to the grief of the collective and ranges through time and space. In the sweeping novel Europa (Europe; Albert Bonniers Förlag), Maxim Grigoriev turns the Continent itself into literature and challenges the romantic image of Europe as proud, open and cosmopolitan. And Ali Derwish’s debut, Saddam Husseins nya roman (Saddam Hussein’s New Novel; Albert Bonniers Förlag, 2021), is a work of poetry that blends the imaginary with the documentary, sending the ghost of the Iraqi dictator to visit a narrator who tries to hold him accountable for his crimes. In this lyrical, innovative book, the conditions of exile are handed down to a new generation.

No, a book about cancer isn’t automatically art, and the same goes for exile or alienation. It is clear, however, that contemporary Swedish literature would be a different and poorer place without migration as a fundamental theme. Time, perhaps, to identify a new backbone?

Kristina Lindquist

Arts journalist and critic

Photo: Julia Lindemalm

Information about the books in this article

Kristina Sandberg

En ensam plats (A Lonely Place), Norstedts, 2021

Rights: Norstedts Agency

Ia Genberg

Detaljerna (The Details), Weyler, 2022

Rights: Salomonsson Agency

Åsa Linderborg

Mig äger ingen (Nobody Owns Me), Atlas, 2007

Rights: Hedlund Agency

Kristian Lundberg

Yarden (The Yard), Symposion, 2009

Rights: Carina Deschamps Agency

Susanna Alakoski

Londonflickan (The London Girl), Natur & Kultur, 2021

Rights: Nordin Agency

Elise Karlsson

Linjen (The Line), Natur & Kultur, 2018

Rights: Norstedts Agency

Tone Schunesson

Dagarna, dagarna, dagarna (Days and Days and Days), Norstedts, 2020

Rights: Norstedts Agency

Isabelle Ståhl

Just nu är jag här (Right Now I’m Here), Natur & Kultur, 2017

Rights: Natur & Kultur

Wera von Essen

Våld och nära samtal (Violence and Other Conversations), Natur & Kultur, 2020

Rights: Natur & Kultur

Amanda Romare

Halva Malmö består av killar som dumpat mig (Half of Malmö Consists of Guys Who Dumped Me), 2021

Rights: Natur & Kultur

Elin Cullhed

Eufori (Euphoria), Wahlström & Widstrand, 2021

Rights: Ahlander Agency

Steve Sem-Sandberg

W (W), Albert Bonniers, 2019

Rights: Nordin Agency

Sara Stridberg

Drömfakultaten (UK: Faculty of Dreams; US: Valerie), Albert Bonniers, 2006

Kärlekens Antarktis (The Antarctica of Love), Albert Bonniers, 2018

Rights: RCW Literary Agency

Balsam Karam

Singulariteten (The Singularity), Norstedts, 2021

Rights: Norstedts Agency

Maxim Grigoriev

Europa (Europe), Albert Bonniers Förlag, 2021

Rights: Albert Bonniers

Ali Derwish

Saddam Husseins nya roman (Saddam Hussein’s New Novel), Albert Bonniers, 2021

Rights: Albert Bonniers